America's warm relations with the Caliphate

In nearly every speech delivered by George Bush nowadays he mentions the word Caliphate.

The re-establishment of the Caliphate is seen as a nightmare scenario by many in the US administration. A state America could never do business with.

But is this necessarily the case?

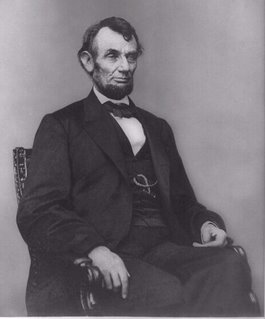

Historically, America had a warm relationship with the Ottoman Caliphate. There were cultural exchanges and trade links between the two countries. Abraham Lincoln, who signed the first treaty between America and the Caliphate in 1862, certainly saw the Caliphate as a state America could do business with.

Details of this relationship between America and the Ottoman Caliphate are as follows.

In 1862, Abraham Lincoln signed the Treaty of Commerce and Navigation with the Ottoman Caliphate.

Sultan Abdul-Hamid II (1876-1909), the Ottoman Caliph who is respected by Muslims throughout the world for his refusal to sell Palestine to the Zionists, had a warm relationship with the United States.

At the very beginning of his period in office, Abdul-Hamid observed the centennial of American independence (1876) by sending a large number of Ottoman books to be exhibited at Philadelphia and subsequently donated to New York University.

Abdul-Hamid was the first foreign head of state to receive an invitation to the Columbian Exposition of 1893, held in Chicago, to honour the four-hundredth anniversary of the discovery of America. Although he did not personally attend, a total of one thousand people from Jerusalem visited the exposition. The World Parliament of Religions held its inaugural meeting in Chicago at the same time, and the Caliph’s representatives exhibited a large number of Ottoman wares and built a miniature mosque.

Abdul-Hamid asked Samuel Sullivan Cox, the American ambassador in Istanbul and the organizer of the first modern US census, to introduce the Muslims to the study of statistics.

Ottoman-American cooperation in foreign policy took place over the Muslim uprising in the US-occupied Philippines. The American ambassador Oscar S. Straus (a Jewish diplomat, incidentally, who was welcomed by the Caliphate at a time when his colleague, A. M. Keiley, was declared persona non grata by the Austro-Hungarian authorities simply for “being of Jewish parenthood”) received a letter from Secretary of State John Hay in the spring of 1899. Secretary Hay wondered whether “the Sultan under the circumstances might be prevailed upon to instruct the Mohammedans of the Philippines, who had always resisted Spain, to come willingly under our control.”

Straus then paid a visit to the Caliph and showed him Article 21 of a treaty between Tripoli and the United States which read:“As the government of the United States of America . . . has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion, or tranquillity of Musselmans; and as the said states never have entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mehomitan nation, it is declared by the partners that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony between the two countries.”

Pleased with the article, Abdul-Hamid stated, in regard to the Philippines, that the “Mohammedans in question recognized him as Caliph of the Moslems and he felt sure they would follow his advice.”

Two Sulu chiefs who were in Mecca at the time were informed that the caliph and the American ambassador had reached a definite understanding that the Muslims “would not be disturbed in the practice of their religion if they would promptly place themselves under the control of the American army.” Subsequently, Ambassador Straus wrote, the “Sulu Mohammedans . . . refused to join the insurrectionists and had placed themselves under the control of our army, thereby recognizing American sovereignty.”

This account is supported by an article written by Lt. Col. John P. Finley (who had been the American governor of Zamboanga Province in the Philippines for ten years) and published in the April 1915 issue of the Journal of Race Development. Finley wrote:

“At the beginning of the war with Spain the United States Government was not aware of the existence of any Mohammedans in the Philippines. When this fact was discovered and communicated to our ambassador in Turkey, Oscar S. Straus, of New York, he at once saw the possibilities which lay before us of a holy war. . . . [H]e sought and gained an audience with the Sultan, Abdul Hamid, and requested him as Caliph of the Moslem religion to act in behalf of the followers of Islam in the Philippines. . . . The Sultan as Caliph caused a message to be sent to the Mohammedans of the Philippine Islands forbidding them to enter into any hostilities against the Americans, inasmuch as no interference with their religion would be allowed under American rule.”

Later, President McKinley sent a personal letter of thanks to Ambassador Straus for his excellent work, declaring that it had saved the United States “at least twenty-thousand troops in the field.” All thanks to the caliph, Abdul-Hamid II.

The international situation today is completely different to that of Abdul-Hamid’s time. America’s obsession with the Muslim world’s resources and its war against political Islam, under the guise of the war on terror, has made it an enemy of Muslims everywhere.

But how long can America sustain its war on terror and its hold on the Middle East?

America’s international standing has been shattered by the Iraq war. It continues to pump $billions in to this war with no real end in sight. This huge drain on the American economy cannot continue indefinitely.

With the imminent establishment of a Caliphate in the Muslim world America needs to make some difficult choices. Either it can continue its hostility towards the Muslim world, dragging it deeper in to an unwinnable war, or it can sign a treaty with the Caliphate withdrawing its armed forces in exchange for continuing oil supplies. Such a treaty would be humiliating on both sides given the massive hostility between the two counties, but better that, than more innocent blood is shed.

0 comments:

Post a Comment